Darzi’s diagnosis might be missing a trick

- Health inequalities

- Hospital waiting lists

- Digital health and care

- Communication and administration

Just days after the general election, our new Secretary of State for Health and Social Care boldly declared that the NHS is broken.

Some of the commentariat were worried this statement of the bleeding obvious might damage staff morale, or undermine public confidence. On the contrary, many of those I have spoken to since have welcomed Wes Streeting’s honesty about the challenge in front of us.

The question is, where is the NHS broken and why? This is the question Lord Darzi has been asked to address in his rapid review of NHS performance. In essence, he has been tasked by the Secretary of State to provide a differential diagnosis, to determine which of the many problems the NHS currently faces is driving poor performance.

Off to a good start

I was encouraged by Lord Darzi’s piece in the BMJ where he said in his review he was particularly interested in how the NHS performs for society’s most vulnerable. “After all, at its heart the NHS is a moral endeavour: it exists to ensure timely access to high quality care for all, based on clinical need rather than financial means.”

And having contributed to the review over the last few weeks I know that his team have indeed been engaging with numerous voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) organisations and the patient voice sector in particular. This has run alongside a call for written evidence which we and many others will have responded to.

The review has also commissioned focus groups with specific communities of interest, including people with physical disabilities, those experiencing mental health challenges and those acting as unpaid carers. All of this points to them getting some good qualitative input.

However, it was also clear that the review would draw heavily on system level performance data, perhaps too heavily in our view.

The Swiss cheese problem

In mid-August we brought together 63 National Voices members (not too shabby given it was the height of holiday season) to compare notes on the review’s progress.

It was clear those who could, had diligently followed the review’s process and submitted evidence in the form of graphs and charts. But for many more, particularly those who work with some of the most marginalised groups, they were asking about what will happen in instances where there is no data. As one individual put it, NHS performance data is “like Swiss cheese”, it’s full of holes.

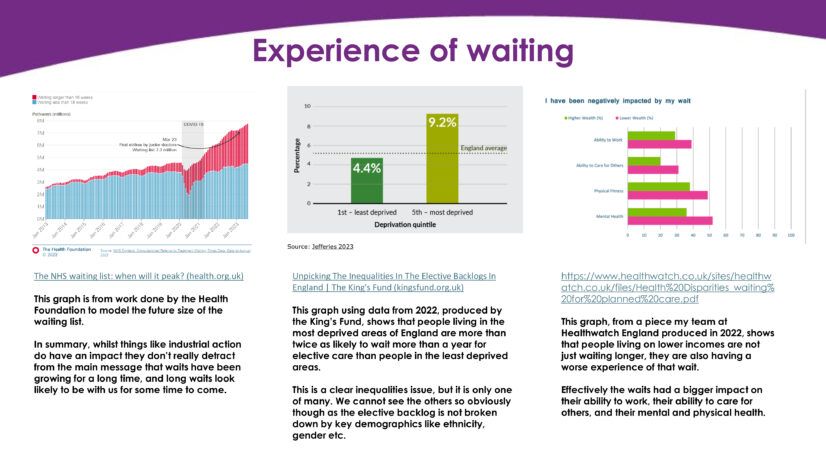

Take the elective backlog for example. There was a strong sense the review will focus on the size of the list, and variation in how quickly different systems and providers are tackling it. Yet there will be little to no analysis of who is waiting longer, and how this is impacting them. This is despite research (which we pointed to in our evidence) showing that long waits are likely to be with us for some time, that people in the most deprived communities are more likely to wait longer and ultimately the negative impact of long waits is greater on these people.

If you look at performance against the elective backlog through an equalities lens, it would paint a very different picture. And as a result, the policy solutions the Government might put in place in the new NHS 10 year plan would likely be very different too. This is particularly true if they want to achieve key manifesto commitments around reducing the gap in healthy life expectancy.

Not all about electives

So many people and conditions will be missing from Lord Darzi’s diagnosis because they don’t appear in national datasets or the ways we analyse them at the moment. Here were just a few examples that stood out from my conversation with members:

- There are queues for care everywhere for physical and mental health, with significant interconnection between the two for many patients. The Darzi review needs to consider patient level data side-by-side to understand how a lack of joined up care is driving demand across the system.

- Official data might show how new initiatives like virtual wards have achieved a system objective such as freeing-up hospital beds, but it will not show the impact on family carers, or the cost implications for people who may not be able to afford to run equipment at home.

- Compassion in Dying talked about their survey, where 1 in 4 bereaved people said that a loved one had been given a treatment they would not have wanted. This is being driven by poor system records on people’s wishes around dying.

- Similarly, the Accessible information Standard requires services to capture and meet people’s communication needs, but poor implementation of this means many care needs go unmet but are invisible when assessing system performance.

- Clinks talked about the importance of intersectionality, highlighting that 9% more people died of cancer in prison than in the community. But given the overall numbers are small, this inequality goes unnoticed.

Future accountability

Lord Darzi’s team will clearly have their hands full making sense of all the evidence that has been submitted. Our ask of them is to take a moment and ask hard questions of whether there are important gaps in what they end up reviewing. Ask “what is the data not telling us”.

And if it is inequalities that Lord Darzi wants to address, then he must conclude that we have a massive problem with data and analysis in the NHS.

Firstly, we don’t capture and share enough demographic data. Secondly, we don’t interrogate data enough and ask follow-up questions through research. Thirdly, we then don’t use data to ensure accountability for outcomes rather than processes.

The NHS has multiple problems, and we need good data on each of these not just to diagnose what’s going wrong but to monitor things as they develop to optimise the solutions.